And how it affects your audio quality.

In the audiophile industry, there is an endless list of topics that spark debate. Contentious topics like expensive cables and high-resolution (hi-res) audio are some that especially rile up the community.

The definition of hi-res audio states that any music file recorded with a sample rate and bit depth higher than 44.1kHz/16-bit is considered high definition (HD) audio.

In this article, we will cover the fundamentals of sample rate and bit depth along with their impact on perceived audio quality.

We will also touch on another concept: bit rate. Bit rate, or bitrate, is commonly used to describe audio stream quality for music streaming services.

How Is Sound Digitally Recorded?

When sound is produced, it creates a pressure wave that propagates through the air. If the diaphragm of a recording device, such as a microphone, is nearby, the pressure waves in the air create a vibration in the diaphragm. Through the magic of transducers, this vibration, in turn, creates an electrical signal that varies continuously with the waves in the air.

This continuous and proportionate variation is where the term “analog” comes from.

The signal created by the diaphragm is often not strong enough on its own. Typically, a preamplifier first boosts the signal so that it can be recorded in a number of ways.

Throughout history, various materials have been used to record and store analog signals. This includes wax, vinyl disks, and magnetic tapes. Eventually, digital records were introduced and became commonplace.

Digital systems (ones and zeroes) record analog signals (continuously variable values) by sampling them.

By grabbing enough samples of an incoming analog signal and saving it into memory, digital records are able to capture and later on reproduce said signal.

A typical digital audio recording has as many as 44,100 samples every second. However, it is not unusual to see 96,000 samples a second with some digital audio formats.

There are several types of sampling methods but Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) is the de facto standard.

What is Pulse Code Modulation?

PCM serves as the industry standard for storing analog waves in a digital format. In a PCM stream, the amplitude of the audio is sampled at a uniform interval. PCM is non-proprietary so anyone can use it for free!

However, it is uncommon to find audio in PCM format due to two reasons:

- File size

- Playback compatibility

File Size

As PCM is uncompressed, the file size of the recorded audio is massive. It is possible to compress audio files using lossy or even lossless compression algorithms to retain the fidelity of the audio while reducing the file size.

Dolby and DTS are lossy audio compressions which are often used for this purpose as they’re capable of reducing PCM audio file sizes by as much as 90%.

Unfortunately, the way that Dolby and DTS encode PCM channels into a bitstream for storage and then decode it back for playback is not perfect. The resulting audio, though smaller in file size, isn’t always as clean and crisp as the original, resulting in a drop-off in accuracy and quality.

Lossless formats such as Dolby Digital TrueHD and DTS-HD, however, keep the Bitstream vs. PCM debate alive and well. They are capable of decoding the PCM audio signals exactly as they were originally captured.

Playback Compatibility

Unfortunately, popular operating systems (OS) do not support the playback of PCM files natively. IBM and Microsoft defined the Waveform Audio Format (WAV) format for Windows OS while Apple used the Audio Interchange File Format (AIFF) for the Macintosh OS. Both formats are just a wrapper around the PCM audio format with additional audio information like author profile and title of the track, etc.

Fidelity Representation

The fidelity/quality of a PCM stream is represented by two attributes:

- Sample Rate

- Bit Depth

These two attributes indicate how accurate the digital recording is to the original analog signal.

What is Sample Rate?

Think back to animated films from a couple of decades ago.

Films were just slides of still images being shown one after another to create the illusion of movement. The speed of the transition determined how smooth the resulting animation was. The faster the transition, the better the illusion of animation.

The speed of the changing slides is just like framerate when it comes to modern video.

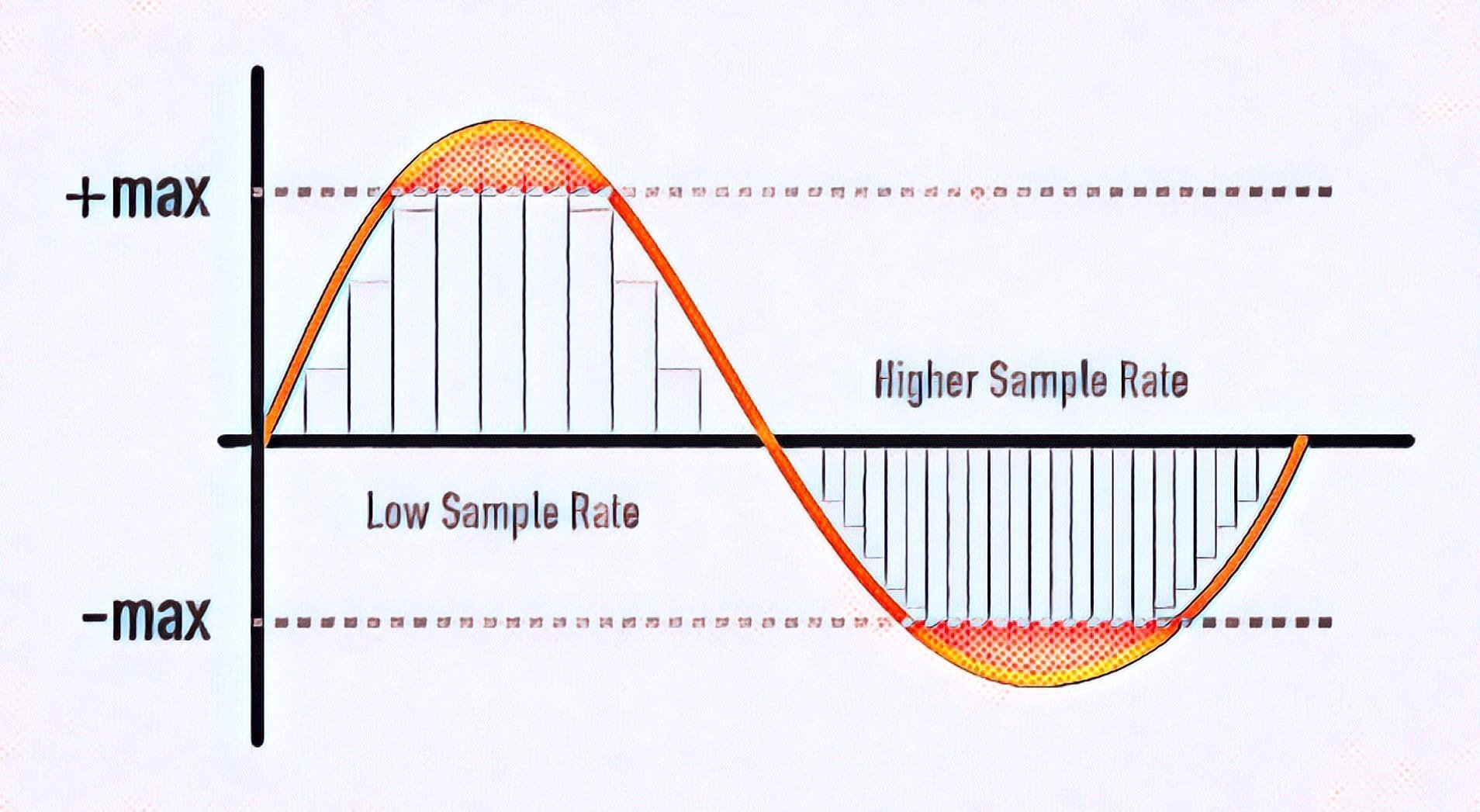

In digital audio recordings, sample rate is analogous to the framerate in video. The more sound data (samples) gathered per period of time, the closer to the original analog sound the captured data becomes.

In a typical digital audio CD recording, the sampling rate is 44,100 or 44.1kHz. If you’re wondering why the frequency is so high when the human ear can only hear frequencies up to 20kHz at best. It’s because of the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem.

Nyquist Theorem

Commonly referred to as the Nyquist theorem or Nyquist frequency, this states that to prevent any loss of information when digitally sampling a signal, you have to sample at a rate of at least twice the highest expected signal frequency.

Other examples of common sampling rates are 8,000 Hz in telephones and anywhere between 96,000 Hz to 192,000 Hz for Blu-ray audio tracks. A sample rate of 384,000 Hz is also used in certain special situations, like when recording animals that produce ultrasonic sound.

What is Bit Depth?

Computer stores information in 1 and 0s. Those binary values are called bits. The higher the number of bits indicates more space for information storage.

When a signal is sampled, it needs to store the sampled audio information in bits. This is where the bit depth comes into place. The bit depth determines how much information can be stored. A sampling with 24-bit depth can store more nuances and hence, more precise than a sampling with 16-bit depth.

To be more explicit, let’s see what is the maximum number of values each bit depth can store.

- 16-bit: We are able to store up to 65,536 levels of information

- 24-bit: We are able to store up to 16,777,216 levels of information

You can see the huge difference in the number of possible values between the two bit depth.

Dynamic Range

Another important factor that bit depth affect is the dynamic range of a signal. A 16-bit digital audio has a maximum dynamic range of 96dB while a 24-bit depth will give us a maximum of 144dB.

CD quality audio is recorded at 16-bit depth because, in general, we only want to deal with sound that’s loud enough for us to hear but, at the same time, not loud enough to damage equipment or eardrums.

A bit depth of 16-bit for a sample rate of 44.1kHz is enough to reproduce the audible frequency and dynamic range for the average person, which is why it became the standard CD format.

Should You Always Record in 192kHz/24-bit?

Although there are no limits to sample rate and bit depth, 192kHz/24-bit is the gold standard for hi-res audio. (There are already manufacturers touting the 32-bit depth capability, eeks!) We will use 192kHz/24-bit as the reference for the pinnacle of recording fidelity.

So when is such fidelity required?

We know that the higher the sample rate and bit depth, the more similar our digital signal will be to the original analog signal. But it also gives us extra headroom.

Extra Headroom

Headroom refers to the difference between the audio signal’s dynamic range and what’s allowed by the bit depth. It’s kind of like driving a truck that’s 3 meters high through an overpass with a vertical clearance of 5 meters. This gives you 2 meters of headroom to work with, just in case you have an unusually tall load to haul.

Sampling in 16-bit gives audio engineers a dynamic range of 96db to work with. On the other hand, 24-bit ups the dynamic range to as high as 144db, although, realistically, most audio equipment can only go as high as 125db.

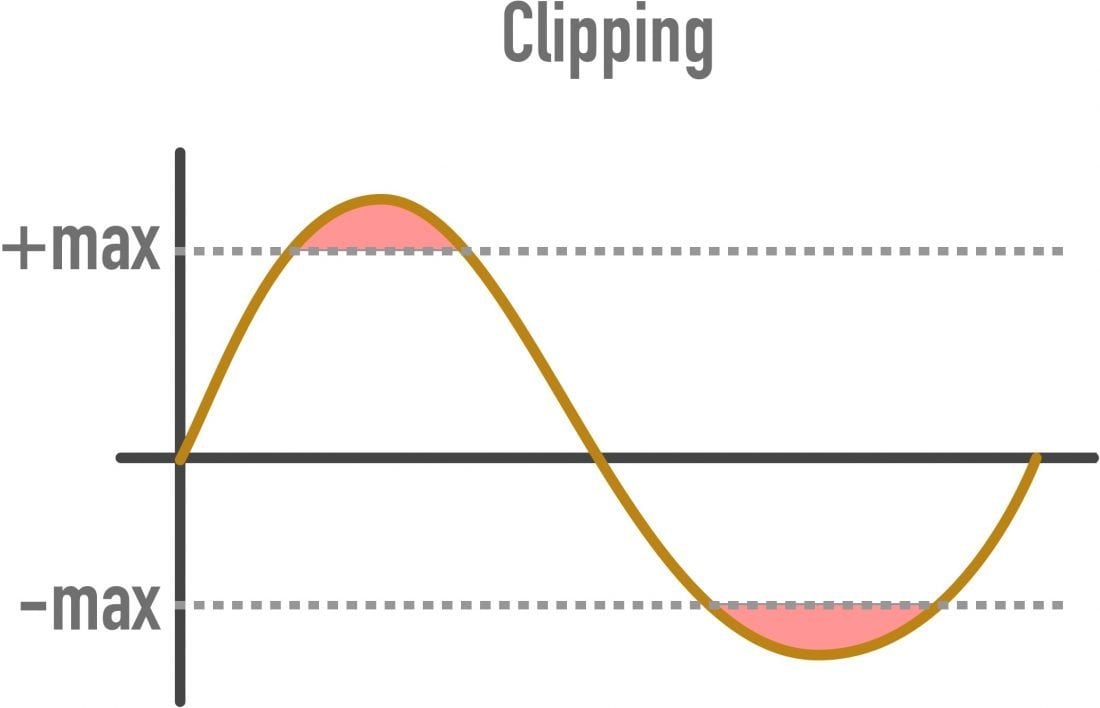

With the extra headroom, audio engineers can minimize if not eliminate the possibility of excessive noise or clipping, which is when sound waves essentially become flattened and cause audible distortion.

Clipping happened when the incoming electrical signal cannot be represented fully numerically. This can happen when the bit depth is shallow.

As the possible signal range of professional audio equipment is much larger than what the average person can hear, using 24-bit allows audio professionals to cleanly apply the thousands of effects and operations involved in mixing and mastering audio to make it ready for reproduction and distribution.

Larger File Size

Other than the potentially redundant headroom, a higher fidelity recording creates a much larger file size.

File Size Calculation

Just to give you an idea of the difference in file size, let’s try and come up with a hypothetical scenario involving a five-minute uncompressed song.

1) First, calculate the bit rate using the formula sampling frequency * bit depth * No. of channels.

- 44.1kHz/16-bit: 44,100 x 16 x 2 = 1,411,200 bits per second (1.4Mbps)

- 192kHz/24bit: 192,000 X 24 X 2 = 9,216,000 bits per second (9.2Mbps)

2) Using the bit rate calculated, we multiply it by the length of the recording in seconds.

- 44.1kHz/16-bit: 1.4Mbps * 300s = 420Mb (52.5MB)

- 192kHz/24bit: 9.2MBps * 300s = 2760Mb (345MB)

Audio recorded in 192kHz/24-bit will take up 6.5x more file space than one sampled at 44.1kHz/16-bit.

So when do you need to record in 192kHz/24-bit?

It’s all down to what you want to do with the audio recording. Do you want to manipulate the recording and do you have unlimited memory storage? Then 192kHz/24-bit should be a no-brainer. But if you are intending to stream your music to your listeners, 192kHz/24-bit will suck up your listener’s bandwidth and rack up their internet bill.

Does 192kHz/24bit Ensure a Superior Listening Experience?

Not really.

Chris Montgomery, a professional audio engineer and the founder of the Xiph.Org foundation, provides an in-depth and technical explanation on why sampling in 192kHz/24bit doesn’t necessarily result in a superior listening experience.

He uses a combination of signal processing and how we humans perceive audio to help explain why sampling in 192kHZ/24bit makes no sense, while also giving readers an idea on how to conduct their own listening tests at home to try and verify things on their own.

You can check out the article by Chris.

Our opinion is that the law of diminishing returns applies to sample rate/bit depth. Once you hit a certain threshold, the marginal improvement in sound quality becomes smaller and smaller until it becomes negligible.

What Is Bitrate?

Bitrate (or bit rate, if you prefer) refers to the number of bits conveyed or processed per second, or minute, or whatever unit of time is used as measurement.

It’s kind of like the sample rate, but instead, what’s measured is the number of bits instead of the number of samples.

Bitrate is used more commonly in a playback/streaming context than a recording one.

The term bitrate isn’t exclusive to the audio industry. It is also prevalent in multimedia and networking. However, in music, a higher bitrate is commonly associated with higher quality. This is because each bit in an audio file captures a piece of data we can use to reproduce the original sound.

In essence, the more bits you can fit into a unit of time, the closer it comes to recreating the original continuously variable sound wave, and thus the more accurate it is as a representation of the song.

Unfortunately, a higher bitrate also means a bigger file size, which is a big no-no when storage space and bandwidth is a concern, such as with music streaming services like Apple Music and Spotify.

Music Streaming Services

From the above section, we see that to stream an uncompressed 5-min song recorded in 44.1kHz/16-bit, it will take a bitrate of 1.4Mbps which is a significant amount of bandwidth.

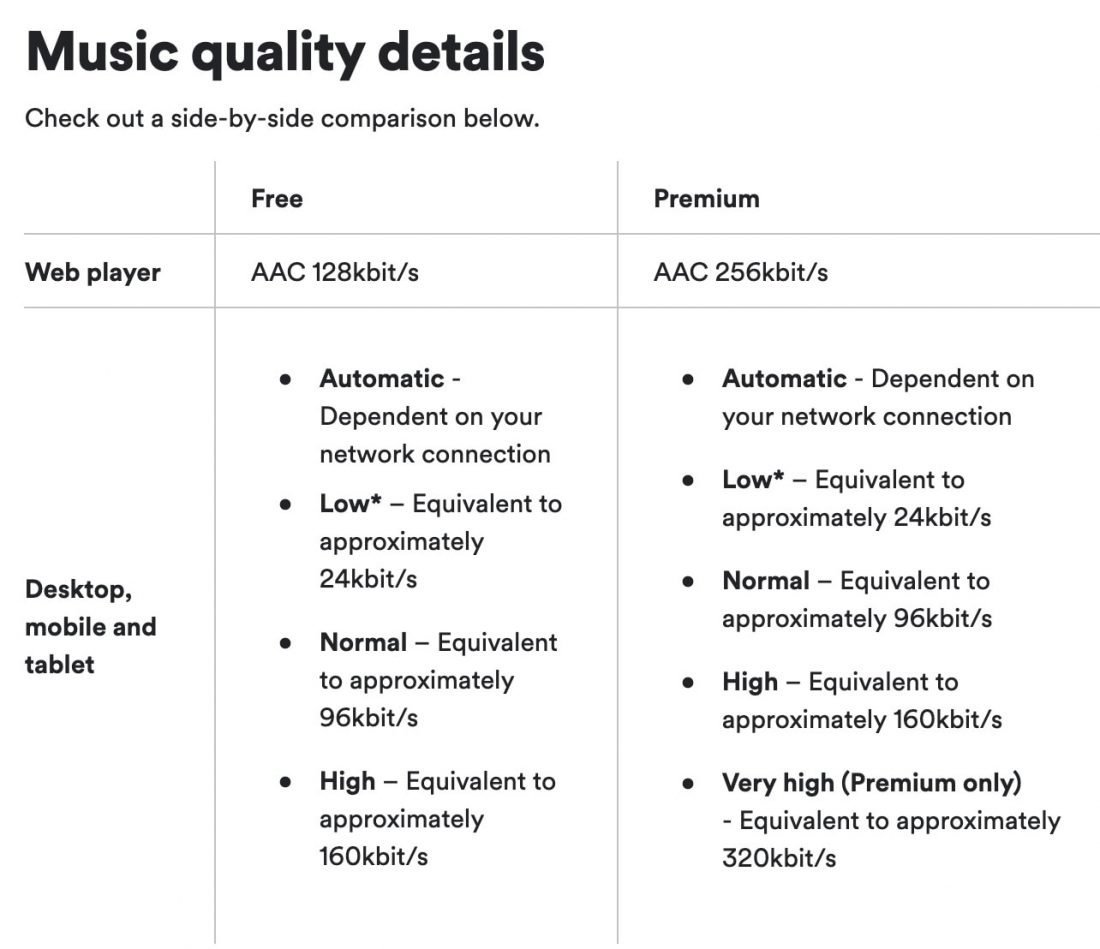

Apple Music and Spotify circumvent this bandwidth issue by compressing the audio. Of course, file compression doesn’t come without consequences. For starters, Spotify limits the bitrate of audio files to 160kbps for desktop users and 96kbps for mobile users. However, premium subscribers have the option to listen to 320kbps audio on a desktop. Meanwhile, Apple Music subscribers are “limited” to a bitrate of 256 kbps.

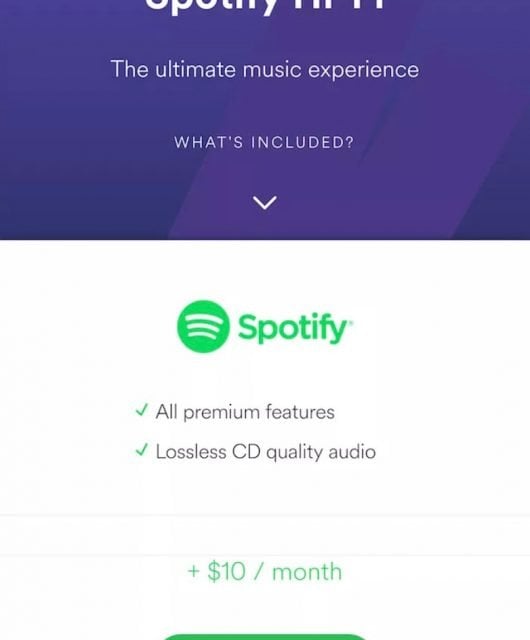

There are also audio streaming services for those who prefer to listen to music with higher bitrates.

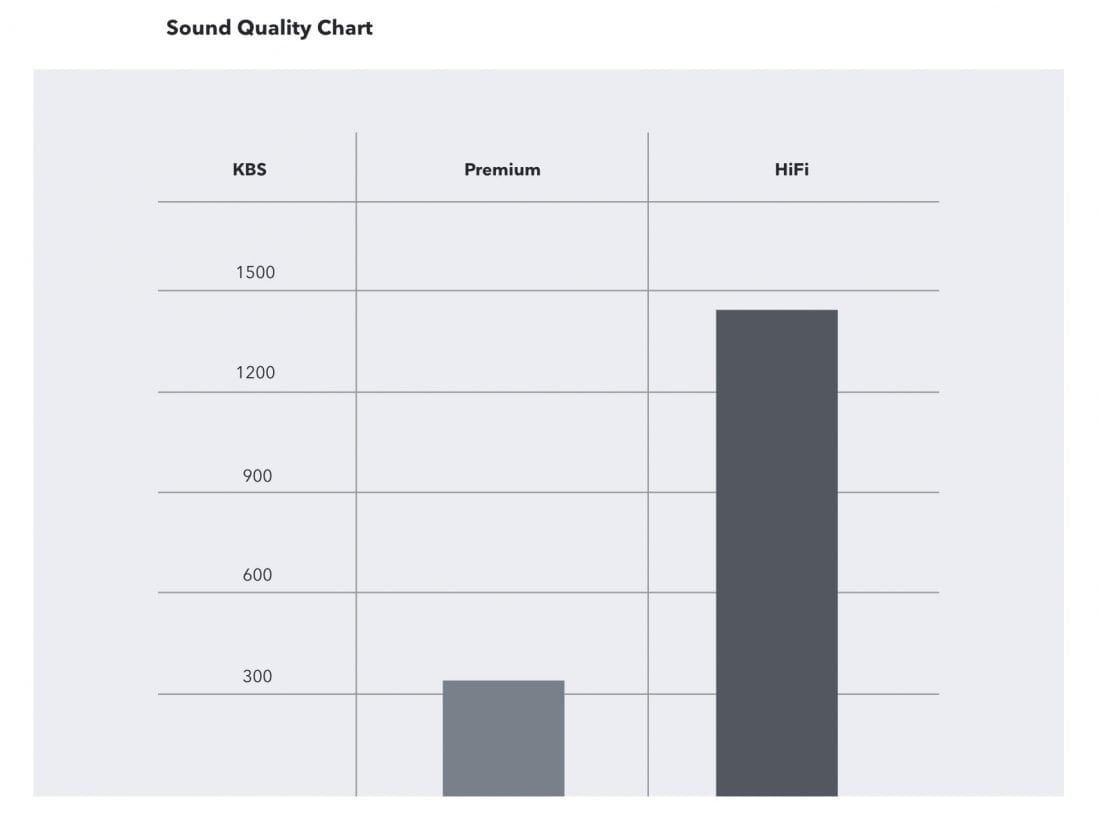

Both TIDAL and Qobuz Sublime+ are widely considered the go-to audio streaming services for those who prefer the best audio streaming quality, with Hi-FI options available for a monthly subscription of $19.99.

TIDAL supports 44.1kHz/16-bit FLAC files that can be stream at a bitrate of 1411kbps.

Of the two, the TIDAL Hi-Fi subscription offers more value for the money. This is because you gain access to a huge library of high-quality FLAC files, as well as 50,000 master-quality songs compressed using the proprietary Master Quality Authenticated (MQA) technology for better sound quality.

Does High Bitrate Guarantee Superior Listening Experience?

Given our example earlier, a typical five-minute 44.1kHz/16 bit song would have had a file size of 50+ megabytes uncompressed.

The MP3 codec was developed to solve this problem by making it possible to compress CD-quality audio without a loss of quality. Early MP3 encoders started off with 128kbps or 192kbps before eventually moving on to 320kbps to compete with other codecs. However, in audio streaming, Ogg Vorbis (Spotify) and AAC (Apple Music) are used.

It’s open source, in the public domain, and delivers high quality relative to the bandwidth required to stream it. We tried out several different file formats and did another shoot out a couple of years ago, and the Ogg Vorbis format came out on top.

The obscurity of the format isn’t so relevant in that users never see the files themselves, so if for some reason another format came into prominence that delivered a better ROI, it isn’t difficult to change to that new format – Spotify’s former Vice President.

Circling back to Chris Montgomery’s explanation, we now know that anything north of 192kbps on a decent encoder doesn’t really matter — the average human ear simply isn’t precise enough to be able to tell the difference.

This means that any music at a bitrate of 192kbps or higher becomes indistinguishable from its original audio analog as long as it was properly encoded in an Ogg, MP3, AAC, or FLAC audio file.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that a high bitrate isn’t useful. It does help guarantee a superior listening experience. However, this only applies in specific situations. For example, if you have a complete Hi-Fi audio system that can take advantage of the minute improvements in audio quality when streaming Hi-Fi audio files.

In general, the casual listener using the average headphone won’t benefit from streaming audio north of 192kbps.

Conclusion

In summary, sample rate is the number of audio samples recorded per unit of time and bit depth measures how precisely the samples were encoded. Finally, the bit rate is the amount of bits that are recorded per unit of time.

That wasn’t so hard now, was it?

Hopefully, we helped clear up some of the mysteries surrounding sample rate, bit depth, and bit rate using our guide.

Going forward, you should now be able to think critically when someone tells you how much “clearer” an audio file sounds based on its encoding process. More importantly, you should now find it easier to find the best audio formats and streaming services for your needs.

Nice article, thank you.

Nice? Are you joking? There isn’t a “bit” of useful information. It talks about Nyquist but doesn’t mention its significance and why 44kHz is enough for final playback mediums (CDs, flac files). It has some *very* misleading stairstep graphs just above discussing digitisation, but as anyone who knows how this works, that is in and of itself misleading. “The digital sound wave is like a snapshot of the original audio signal. The closer the sampled sound wave looks like the original sound wave, the higher the fidelity of the digital sound wave.” – we know that isn’t a precise definition because Nyquist says that provided we are twice the highest frequency there can only be *one* analog signal that will fit the digitisation. Isn’t that perfect fidelity?

You are totally correct. Unfortunately the link to the original article by Monty is broken. Do you know where it can be found? I need to educate my sun who laps up the 192kHz/24bit nonsense.

Not nonsense. Human hearing in the 20 to 20,000 cycle range is only accurate when you’re talking about test tones or continuous sound.. Not impulsive sound which is what we hear in the real world. So a circular logic starts. That’s fun to follow for a while and then have to get off and go back and enjoy my 24-bit, 196 kHz samples in music streaming where the ability to strip away all jitter is only possible there.

Vinyl full of bad vibrations, CDs never spin at the same speed as the circumference changes and both have gone As far as they can go. Music streaming in the high resolution format is awesome and compared to 16 bit if you can’t hear the difference it’s because you’re using a system that will resolve much…Probably round wires that look like something you can tow a car with? Electrical engineers say opposite of what it should be, marketing to people who like to show off their gear w mines bigger! LOL! Try a mega micro/N sound audio ribbon wire, also saw that Mapleshade Audio did not advance stuff. My system has a super Twitter that goes to 50 kHz and if you take it off you hear what you’re missing for those who still believe we’re limited to 20,000 cycles..

@”Dash I All”

Prologue : I actually found the article pretty informative on a fast first read, but then I’ve done several engineering credits in communication theory, so maybe the gaps lay people see are not evident to me.

> because Nyquist says that provided we are twice the highest frequency there can only be *one* analog signal that will fit the digitisation. Isn’t that perfect fidelity?

Well not quite – you get noise introduced by sampling in time and by sampling of the waveform amplitude – ie temporal and spatial noise.

Nyquist’s theorem states (from memory, but I think this is 99% correct) that the sampling frequency must be strictly greater than twice the highest frequency in the signal. Consider sampling a pure sine wave of 1 Hz at 2Hz. You will always sample the same amplitude but with alternating sign. You would incorrectly deduce a sine wave of the wrong amplitude, and even possibly a steady zero value.

The closer the sampling frequency gets to twice signal bandwidth, the longer time is required of the sampled signal. It’s something like : if you oversample by 1% (that is sample rate = 2.02 * bandwidth) then you need something like 100 periods to reconstruct with something like 1% SNR.

The next problem is no real world signal has a finite bandwith, and no real world filter can reduce it to a finite bandwidth either. There is always noise due to sampling since there is always signal spectrum above the Nyquist frequency.

And then you get noise to spatial (amplitude) sampling. The rms value of this noise is something like 1/12th the signal range of one bit, and that assumes the ADC is perfect (even without signal noise the ADC sampler has internal conversion errors).

So forget about “perfect fidelity”.

Anyway it seems the latest trend is to add artificial scratches to modern music to make it sound more authentic. So who needs anything more than 60 dB ?!

“It is generally considered that a good signal to noise ratio is 60 dB or more for a phono turntable, 90 dB or more for an amplifier or CD player, 100 dB or more for a preamp.”

Great article and thanks for breaking things down to smaller byte size 😉

I see what you did there. Hope it has enough depth for you.

Bit depth does not measure “how precisely the samples were encoded” but defines how far (decibel wise) quantization noise is from audible spectrum.

To the OP’s question at the top of the article, the basic problem with “Yes, 192/24 Files Do Sound Better” is that the author doesn’t perform double-blind tests. He records the concerts; he does the downsampling; he does the listening. And he plays his recordings for manufacturers and audiophiles (and no doubt records the results). His declaration that “none have found the 44.1 files to be superior” is telling. The question should be whether anyone agreed with him that the 192 files sound better. He doesn’t say yes, which is odd. Surely he’d mention it. But he doesn’t.

He says instead he’s basing his findings on listening tests, not theories. There’s a difference, of course, between a theorem and a theory. The signal theorem is something that is proved. It is accepted as a truth. The author, by contrast, offers some questionable findings to support his opinion. He’s the one with the theory.

As “24/192 Music Downloads …” nicely explains, 192kHz digital music files offer no benefit. And 24-bit depth, while not harmful, is simply unnecessary. It’s as useless as 192kHz sampling when it comes to playback.

When it comes to playback: That’s the key. If you’re not terribly interested in how music is recorded and produced in the studio, if you simply want to know whether “hi-res” music files sound better than CD-quality files from the same source, they don’t because, well, they can’t. Like the oversampling wars that erupted among the makers of CD players in decades gone by — “We’ve got 8x oversampling!” “We’ve got 16x!” — more is not always better. Sometimes it’s just overkill. Extremely profitable overkill.

Great commentary. Thanks.

Nice Expanded Sir,Let me know 44khz16bit*2, can I

Modulate That My Home Made FM Transmitter.

Thanks.

Great article. well organized. Not sure if you still read these comments anymore, but could you explain bit depth a bit more or know of more resources to study this?

Thanks for the explanation. It’s always puzzled me, a non audiophile what all of these darned numbers meant!

As an aside, I’m pretty saddened to find out Mickey Mouse is not real.

Thanks. Now I understand!

Author confuses sample rate with bit rate at the end, 192Khz vs 192kbps.

Still a great introductory article that taught me enough to tell the difference!

Chris’ excellent article can be found here:

https://web.archive.org/web/20200426050432/https://people.xiph.org/~xiphmont/demo/neil-young.html

The conclusion should be that 44/16 exceeds what any listener could possibly hear, which is 1.4mbps uncompressed. Anything below that relies on compression, which is the possible area for debate (and premium streaming audio).

This is a useful article.

I have a few questions: Here’s the premise: I listen from Spotify premium on my MacBook. So I guess Spotify is sending me bits via the internet with a bitrate of 320 kbit/s. The data that Spotify is sending to my computer is compressed.

Question 1: Does spotify (the software) decode the compressed ogg vorbis signal into a PCM signal and then it sends that signal to the audio deamon of my computer, and then the audio deamon sends that uncompressed PCM signal to the DAC? If yes, then I guess it’s Spotify that decides the final sample rate and bit depth of the output signal (e.g. 44.1/16)?

Question 2: If the above answer is yes, then what happens when I set the DAC to play at 48/24 (from the MIDI settings of macbook)? I can still hear the sound very well. What happens in this case? Spotify outputs 44.1/16 but the audio deamon converts that to 48/24 before sending it to the DAC? If the answer is yes again, I guess there could be a quality drop since 48 is not a multiple of 44.1??

So how is it possible to have MP3s with different bitrates then? If you set a sample rate and the sample rate defines a certain amount of information per time, how do you remove part of that information without reducing the sample rate or bit depth?

Lossy compression that’s how. Some music will compress better than others.

In other words, there is not a shred of “real world” perceptible difference between

Aptx and Aptx-HD audio.

great article, thank you!

thank you, advertisements in this page is muted by chromium BTW.

thanks a lot for this clear and valuable information.

Thank you a lot for these precise informations for me, a non-expert. When I see the augmentation of prices in the field of hifi in relation to benefit for the consumer I am satisfied to stay by my ‘old’ vinyls and cds.

Concerning streaming services I’ll survey the development.

There is a difference of audio quality between 44.1kHz compared to 96kHz or 192kHz there is a difference in the three when it comes to musicians of whom are creating the very music in which you the listener and the audio engineers are recording and uploaded the signals. Guitar or sound signals entering these chip processors that convert analog to digital in which either operate on 44.1 or 96kHz. The difference is “latency” you get 0.5-1ms lower latency with 96kHz sampling rate conversions compared to 44.1kHz at 2-3ms. So in theory and or closer to the truth it’s not that the quality is better to the human ear its the music or digital signals being produced by musicians these DSP conversion affect human performance and in fact are reaching the listeners auditory at a faster speed in terms of latency. For a musician’s like myself there’s a big difference between these sampling rates because sampling rates are based on what a processor chip can convert analog to digital and it becomes clock speed from point of a single note played on instruments entering the processor that takes a analog signal per second to point of conversion as it takes a snap shot at either 44.1 or 96kHz. Example I’d like you to play, on your guitar or in your mind, a low E. The sound wave of that low E has a fundamental frequency of 80 Hz. In DSP digital signal processor, that 80 Hz signal is digitally converted and sampled at a rate of either 44.1kHz , 48 kHz or 96 kHz. Think of the sampling process as taking 96,000 high definition snapshots of the signal that become represented by 96,000 different numbers—each of which can be mathematically manipulated. In basic terms the DSP bit size or bit depth is how much information can be stored and the higher the kHz the faster the signal conversion. The listener is also hearing these conversions faster therefore to the listener the tracks recorded with higher sampling rates are hearing better music!

Appreciated your article. Very useful information. However it bears correction on one point.

You said:

Of the two, the TIDAL Hi-Fi subscription offers more value for the money. This is because you gain access to a huge library of high-quality FLAC files, as well as 👉50,000 master-quality songs compressed using the proprietary Master Quality Authenticated (MQA) technology for better sound quality.👈

GoldenSound and others revealed that MQA encoded FLAC Files reduce the quality of files below the level of CD quality. I have carefully auditioned Hifi and have found some of these files are inferior myself. So for the sake of headphonesty. You might take a listen and make a correction.

I subscribe to both Qobuz and Tidal. And audibly Qobuz has superior audio quality over Hifi encoded from Tidal. If you request I can give you some familiar examples where this becomes apparent.

Regards,