Should headphones be a “love at first listen”?

At the end of January 2024, The Headphone Show published a factory tour video where their chief IEM reviewer was visiting the 64 Audio HQ in Vancouver, USA. During an interview, 64 Audio’s CEO, Vitaliy Belonozhko, said that he mostly tests IEMs with fast switching comparisons because otherwise, his brain would get used to the sound.

He restates that he, and others in 64 Audio, believe that the first 5-15 seconds of your sound impression is “the most accurate impression you’ll ever have”.

In response to the video, a Redditor posted in the r/headphones subreddit, asking whether or not brain burn-in actually affects the evaluation and enjoyment of headphones.

This highlights the contrasting views between the IEM manufacturer’s CEO and many audiophiles.

So, in an attempt to settle the debate and answer whether brain burn-in actually matters, let’s look at whether our auditory apparatus actually changes when we wear a certain type of headphones.

Brain Malleability

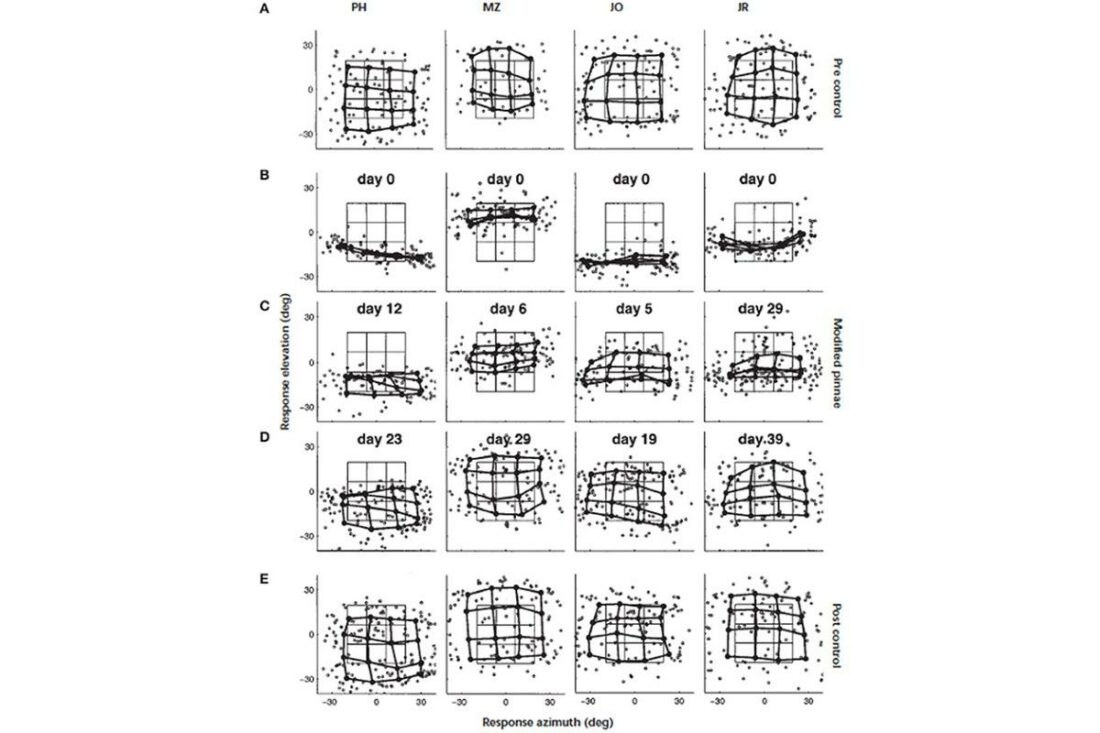

In 1998 a curious research was performed by P. M. Hofman and others. They took four volunteers and inserted small molds inside their conchae. They measured the test subjects’ capability to detect sound direction before their ears were modified and then periodically after living with their new “ears” for a while.

There were a number of findings over the course of the research. However, the most interesting was that all four test subjects had very little trouble adapting to the new concha geometry and restoring their capability to detect sound direction. Some people took longer than others, but all four adapted well.

What really made my jaw drop was the fact that after removing the molds, their ears were all wrong. But, when they immediately switched over to the “stock” concha, they worked as well as before the experiment.

Usually, I use this experiment as a counter-argument to the statement that all people hear differently because they have different sizes or shaped ears.

As it turns out, our auditory apparatus takes into account even changing ear geometry and constantly recalibrates.

Adventures in ABX

During my tenure at Sonarworks, I participated in hundreds of listening tests, both blind and sighted, to determine differences between headphones and different target responses. It’s not an easy job, but someone has to do it – I’ve even fallen asleep a few times during audibility threshold testing.

Generally, target response testing is easy – you put on a pair of headphones and switch between different types of processing. Just push some buttons and assign preference or just show whether you can tell between them at all. Comparing actual physical headphones is very hard.

Our method was to keep one pair on our ears and another pair of headphones on stretched-out arms behind the head. After a short listen, I would slide the new headphones on my head while simultaneously pushing the previous ones down on my neck. Of course, sometimes they would end up on the floor or worse.

Slow Versus Fast

Most of our testing was done by listening to short chunks of audio. We’d cut out and loop a sample from Killing in the Name by Rage Against the Machine and it wouldn’t be longer than 10 seconds. Usually, one or two loops were enough to gauge tonal differences.

Why not longer?

In my experience, major stuff like the frequency response is best evaluated in the first 10 seconds of listening.

After about 30 seconds, the recalibration kicks in, and the auditory apparatus starts adapting to the deficiencies of the device.

Longer listening sessions are also pretty taxing, and ear fatigue tends to creep up. Then everything sounds the same, and you need to take a break. After a short rest, the testing can continue with a fresh set of ears.

Reviewer Blues

As a professional audio writer, there’s nothing I hate more than a decent product. You press “Play” and absolutely nothing sticks out. It’s okay. But where’s the story? Enter long-term listening tests.

As you listen longer, the big things like tonality issues tend to melt away. Instead, you’re able to focus on the minutiae – distortion, dynamics, imaging. Therefore, it’s a game of tradeoffs. I very much get what Vitaliy meant by saying that the initial impression is what matters.

With prolonged listening one risks blinding themselves to the forest by overfocussing on the trees.

Is Brain Burn-in Real?

While there isn’t much research done on how long-term listening tests impact listener preference, it’s well-known that the human auditory apparatus constantly self-calibrates. Anything that self-calibrates will change to a new environment. Even if it’s a pair of headphones.

Other aspects at play might contribute to what’s thought of as long-term brain burn-in.

Some headphones have made me unconsciously choose a certain kind of music that sounds good on them. While I had my Grado SR80i, I’d listen to mostly classic rock and jazz. Metal and electronic music were pretty unbearable on them.

While it takes a really colored pair of headphones or IEMs for your brain to go full “copium”, there’s always some after-image. Especially when a comparison can be done to a known reference. That’s why I keep a calibrated speaker system around – it’s the perfect palate cleanser!