If we have made stones think for us, then what’s keeping us from teaching crystals to sing?

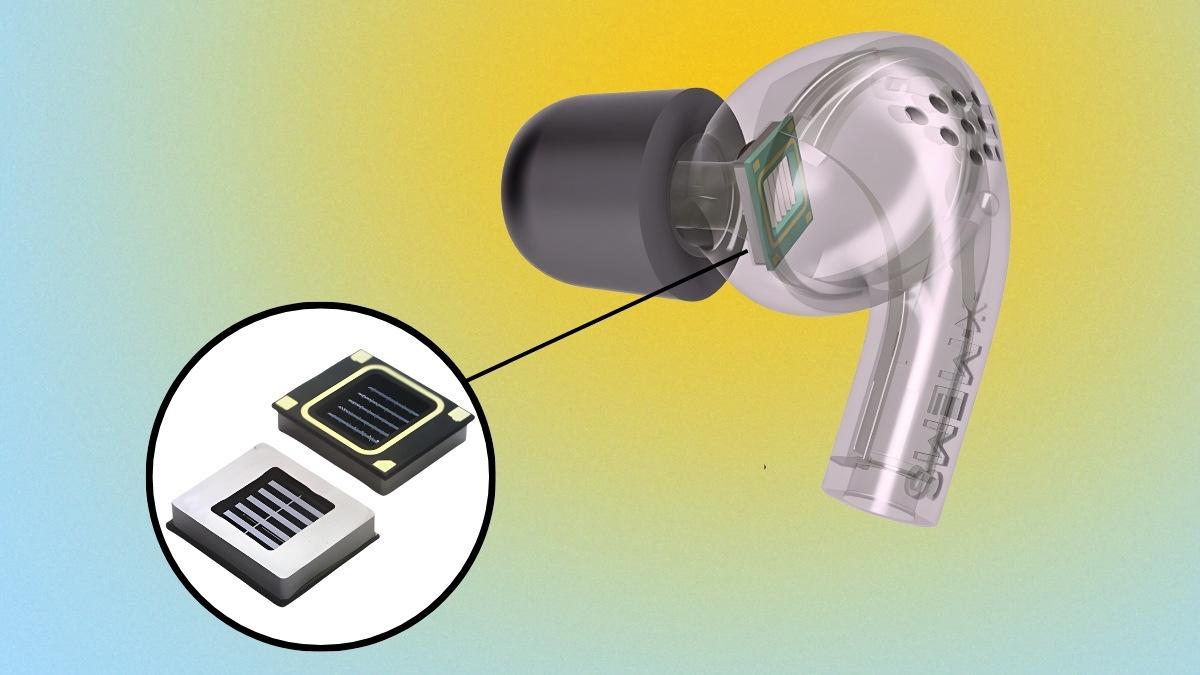

For a couple of years, one of the more popular technologies in many industry and consumer media outlets has been MEMS (microelectromechanical systems) speakers. And now, a growing number of IEM manufacturers are setting aside Balanced Armature drivers with MEMS. These promise smaller sizes, higher fidelity, and a general revolution in audio.

I’ve lived through my share of audio revolutions (remember graphene drivers?), so let’s take a look together at MEMS and see what’s there to actually be excited about!

MEMS is MEMS is MEMS…

For clarity’s sake let’s first get our definitions straight. What are MEMS audio transducers?

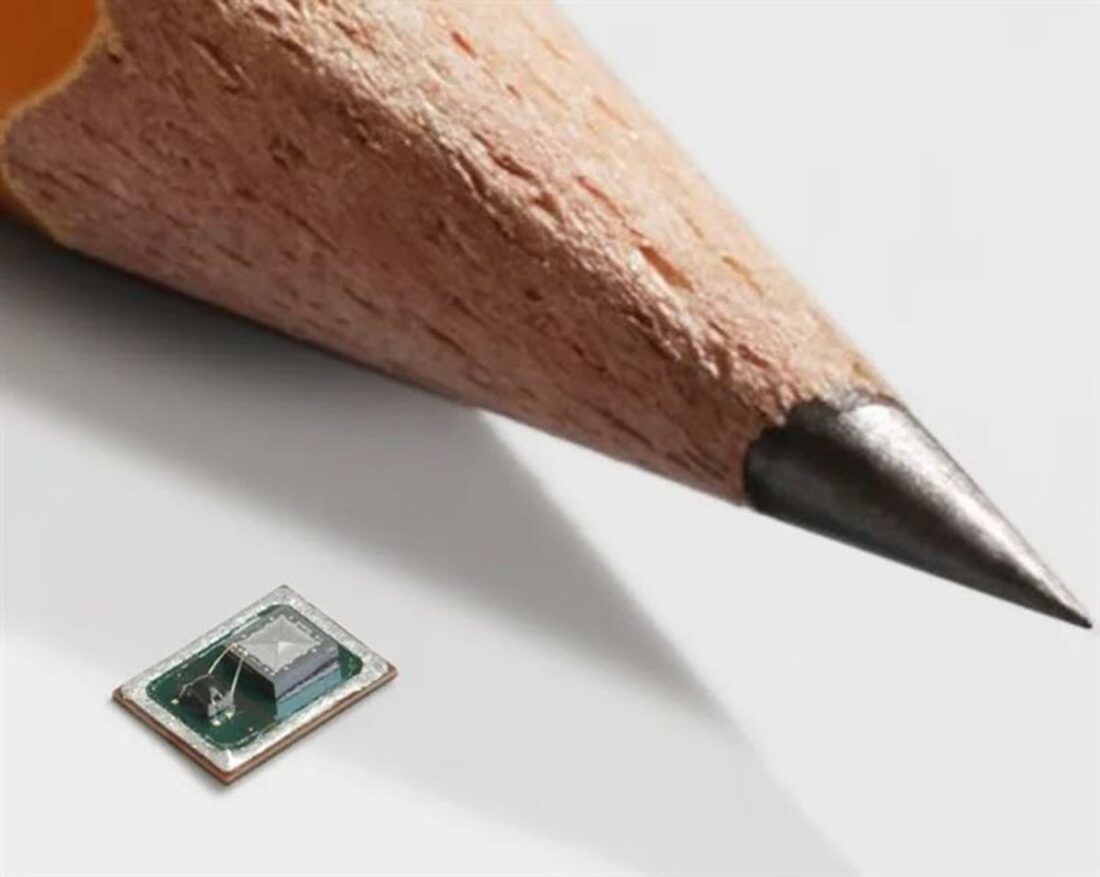

So, only two things are clear – it has to be tiny and made by techniques of microfabrication!

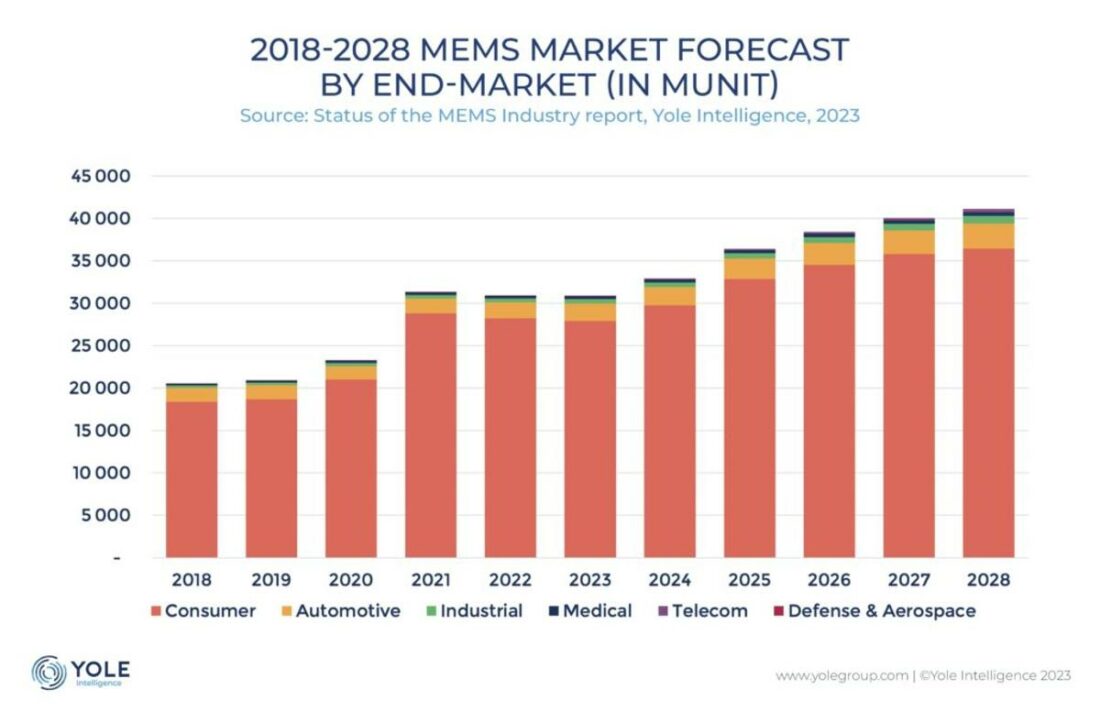

As it turns out, MEMS tech isn’t all about audio, devices like electronics, sensors, and actuators of many other kinds exist in this format.

What makes things even more complicated is that more than half a dozen companies are competing in the MEMS audio segment – USound, TDK, Fraunhofer, Audio Pixels, Sonion, and xMEMS being the most known.

The kicker? They all use different approaches to produce or capture sound.

If someone just calls their transducer MEMS, there isn’t really anything we can deduce apart from that it’s very tiny and manufactured by certain techniques.

How do MEMS drivers work?

So, there are many MEMS devices being developed and made that can make sound. Is there anything common among them?

After looking through what little concrete info is out there, some trends appear.

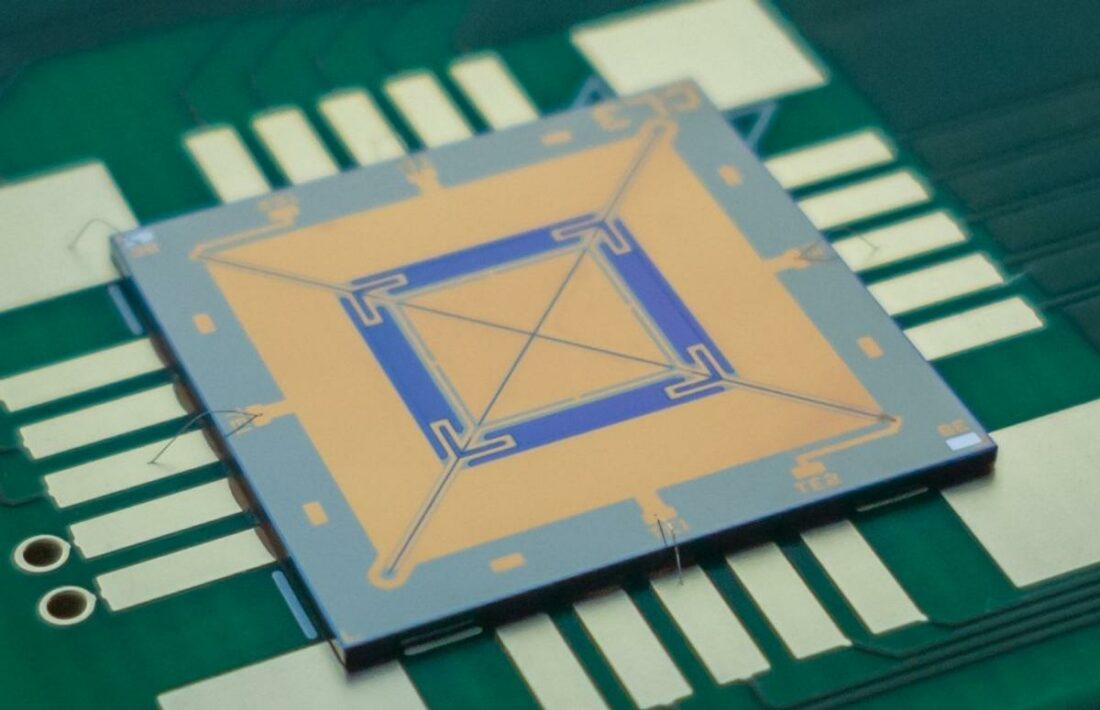

Most of the MEMS audio transducers rely on the piezoelectric effect to make sound.

For reference, piezoelectric transducers use tiny pieces of crystals (usually quartz) that deform when electric current is applied to them. They also can be made to capture sound because they generate electricity if sound waves slightly deform them.

Piezoelectric speakers aren’t anything new – many public address systems use them as well as microspeakers in electronics where fidelity isn’t paramount. Some IEMs also employ them for high-frequency reproduction. The innovation with MEMS is both the size and the manufacturing process.

It’s also worth mentioning that many MEMS drivers have extra electronics on board like an amp or even digital electronics as well to make implementation easier. After all – many MEMS drivers require a bias current and hence cannot be driven directly by conventional headphone amps.

No Replacement for Displacement

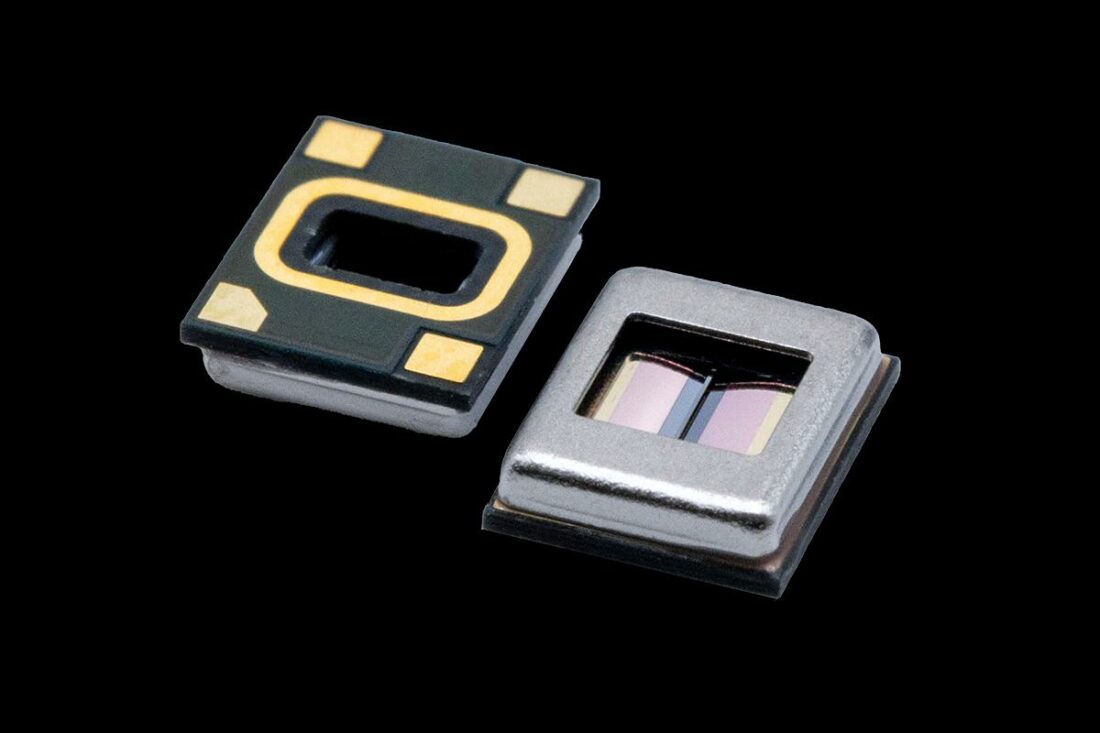

While MEMS speakers are relatively new, their cousins – MEMS microphones have been around for many years. If you have a smartphone or any other device that requires a tiny mic, then there’s a good chance it has a MEMS microphone.

All speakers need to move air. Their ability to do so roughly is the result of two things – effective diaphragm area and piston travel distance. A 12” speaker doesn’t need to move as much as a 5” to produce the same sound.

A piezoelectric MEMS driver has neither the size nor travel capability of, say, a dynamic IEM driver. The tiny sliver of quartz can only move around 0.5mm. This limits both maximum loudness and low-frequency capability. At least unless multiple MEMS drivers are used.

Future-Fi or Just a Fad?

Currently, the easiest way to experience a MEMS driver would be to get a Creative Aurvana ACE 2. They use a 10mm dynamic driver for lows and an xMEMS Skyline driver for highs.

The only all-xMEMS IEM are the Singularity ONI, which were worth $1500 but are now sold out. You’d also have to get the IFI Diablo 2 because, currently, it’s the only amp that can properly directly drive its 48 (!) xMEMS drivers. Not unlike electrostatic headphones in this regard.

As an audio enthusiast, I’m fascinated by the ability of MEMS drivers to respond almost instantaneously to electric signals. The manufacturers promise lightning-fast transients but so far are stingy with the specifics – no real datasheets are available for me to salivate over.

One thing is for sure – there’s a lot of money invested in MEMS tech which is also reflected in the massive PR buzz that’s being generated. The tech has been around since the 1990s, but only now do we have the manufacturing capabilities to bring it to the customers.

As with any silicon substrate fabrication, MEMS requires a huge investment before mass-scale production can start. The promises are lofty and often inflated however, the basic science behind it all holds water. Maybe someday we will get the mythical “fast bass”!